Statistics is not an IQ contest

Read a great line in Seth Godin’s book, Linchpin,

“It’s not an effort contest, it’s an art contest.”

The point being that no one cares how hard you worked, they care how great your product is. Of course, great products tend to result from hard work along the “necessary-but-not-sufficient-condition” lines, but that’s a whole different topic.

This fit with what I have been thinking about statistics a lot lately,

“It’s not an IQ contest, it’s a knowledge contest.”

I read a lot of statistics articles, attend a lot of presentations on statistics – and I see a huge disconnect between these really brilliant people and those who are making decisions on policy, funding and management. This is our fault. Well, maybe not yours and mine personally, but the fault of the discipline as a whole. We spend much of our time researching new statistics, writing papers on the latest developments. Some of these decrease the standard error, or at least give us a more accurate estimate. That’s all good, right?

We spend FAR less time on making sure our results are interpretable to people other than ourselves. In my previous life, I led faculty development workshops on teaching mathematics and science. Many of my colleagues were dismissive of the idea that we ought to work to make our ideas discernible to the average person. One of them actually sniffed dismissively (I didn’t know people did that outside of Victorian novels). He told me that he had gone to the effort to get a Ph.D. and these students, if they didn’t have the intelligence and/or weren’t willing to work hard enough to learn from him, then they all deserved to fail and that people like me were ruining academia.

SIGH. It gave me empathy with a school psychologist I knew who once wrote as a child’s diagnosis “Dyspedagogia”. (Latin for “bad teaching”.) After he was caught out, he refused to change it, too, saying he stood by his professional opinion.

Anyway…. I don’t know if that professor was as brilliant as he thought – he did obtain a doctorate in a scientific field from an Ivy League school – but I really don’t care. It’s not an IQ contest. As for everyone else who is not a statistician, as Sheila Tobias said in her wonderful book by that title, “They’re not dumb, they’re different”.

As a statistician, I KNOW that I see things differently and my job is to explain what I see, and not necessarily in the way it makes sense to me but to make sense to other people.

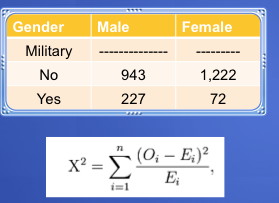

For example, when I look at this:

When I see the table, the formula below automatically pops into my head.

When I see the table, the formula below automatically pops into my head.

Then, I think, that there should be about the same number of males and females saying “yes”.

The total sample is (roughly) evenly divided by gender and about 300 people said they planned to join the military after high school, so the expected value is 150 women.

Subtracting 72 from the 150 one would expect gives a value of about 80, which squared is 6,400.

It is already obvious this is significant.

Really, I don’t get nearly that explicit. What I’m more likely to think is,

“150 – 72 squared is a lot. That’s significant.”

Then I run it in JMP or SAS or SPSS and see that the chi-square is 110, p < .001 and I am right.

Occasionally someone shows me a table like this in their dissertation and the chi-square value is 1.06 and it is non-significant. They tell me this is what the computer gave them. I look at it and tell them.

“Well, then, the computer is wrong.”

The uncomprehending shock on someone’s face when I say this always strikes me as a bit odd, as is their complete amazement when I turn out to be right.

Of course, that just means that somewhere along the line they incorrectly programmed the computer. It happens to everybody.

Yet, people go away shaking their heads in disbelief, and I have a reputation as “that scary smart person in the corner”. Truly, here was the great dramatic insight that popped into my head that lead to the conclusion that their chi-square value was incorrectly calculated. I looked at the table for two seconds and this was my exact thought.

“6,400 is a big number.”

Not very profound, is it? You might be thinking my point here is that I should work back to the steps that led me to that insight. If you are thinking that, you weren’t paying attention to the “different” part. In fact, this is what I did;

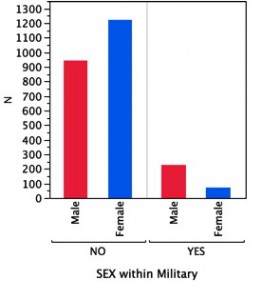

“Take a look at this chart. You can see that about three times as many men plan to enter the military as women. That might not be significant if you had five or ten people, but you can see (on the Y axis), you’ve got over 1,000 people in each group.

“Take a look at this chart. You can see that about three times as many men plan to enter the military as women. That might not be significant if you had five or ten people, but you can see (on the Y axis), you’ve got over 1,000 people in each group.

When you get a fairly large number of people and the difference between the two groups is a factor of three to one then you can be pretty certain there is a relationship between being in that group and whatever the other variable is, in this case the decision to join the military.

Now, this fits with what you already were pretty sure of in this case, which is that men are significantly more likely to enter military service than women.

However, that’s not necessarily the case that the results will always bear out your pre-conceived notions. For example, the next set of results, on race and ethnicity, did not fit at all what we had expected….”

While this might not make me sound as intelligent as going through the chi-square formula (which is really a pretty simple formula, after all), it does accomplish three things:

- I am pretty certain that everyone in the room when I explained this understood exactly what I was saying and could follow my logic.

- Because they had the confidence that they understood exactly what I was saying and how it fit with what they already knew, they agreed with me, they didn’t just go along with me. This is crucially important because if later on I want them to support some initiative based on this information they’re a hell of a lot more likely to do it than if they’re not really sure what I was talking about.

- Having gained some confidence that they can understand what is going on here and that it is not completely random, when we come to the next set of results, which just happens to be contrary to what was expected, I have their attention and I am half-way to having their agreement and support. Come on now, admit it, aren’t you just a little curious to find out what we learned about the relationship to military service to race and ethnicity?

I don’t know if any of this shows how intelligent I am. If anything, I think I might have more claim to intelligence based on the fact that I figured out how to do the chart in JMP only a few minutes after starting to use it. I wanted “male/ female” and “Yes/No” instead of ones and zeros and reasoned that since SPSS has value labels and SAS has proc format, there must be some way to do it. (There is, right click on the column you want. Click on COLUMN INFO then select COLUMN PROPERTIES and then select VALUE LABELS”.

I remember a quote on the definition of intelligence that,

“The essential difference between a genius and a moron is the ability to generalize.”

So, is any of this proof that I’m a genius? I don’t know. I do know that nobody cares.

Nice post, and a cause that as a psychometrician that works in the licensure / certification industry am completed aligned with. In fact, nothing is more off-putting to clients when the pre-eminent expert parachutes into your marker training session to state that he ran esoteric statistical procedure gamma (which he won’t burden you with explaining) and computed value ‘z’ which means that you need one more marker per extended response. Related to this, one of my favourite stats profs in grad school once said to me that we don’t need more sophisticated data analysis methods, we need researchers to design better experiments. Bingo.

I liked the “dyspedagogia” line and quoted it on Twitter. A couple people pointed out that the word origins are Greek. Minor point. I’d like to see the term more widely used.

Well, I don’t speak Latin at all and the only Greek I know is in formulae like alpha, beta, chi, sigma and so on. The person who actually did it said it was Latin but I believe you. I attended a school called Logos High School, which was from the Greek word for knowledge (or so they said!).

What I found really hilarious in the whole story is that after someone figured it out, the school psychologist refused to change it. I asked him about that and he said he called it as he saw it and that there was nothing wrong with the child that good teaching couldn’t fix.

This is my first real visit and read of your blog. What a great find! Lots to think about and funny too. I’ll be baaaaaack. 🙂

Aaaw. Thank you!

SECONDS is a very overlooked film; Ive only seen it once (about 20 years ago) and the scene of the commuter going to work right at the start of the film has stayed in my memory ever since, because it is shot in such an unusual and disturbing way. Just hope that it gets released on R2 DVD at some time.