Every Picture Tells a Story and Why That Matters

Being a professor can build humility. About twenty years ago, I was teaching the third course in the statistics sequence required of all graduate students. The second course had been taught by an adjunct professor, which was FAR less common then than it is now (that’s a whole different post). The first day I started out talking about multivariate statistics (that being the name of the course) and was almost immediately stopped by a student,

“What is that F-statistic you mentioned? We didn’t learn that in the last course!”

Another student interjected,

“Mean square error? We didn’t learn anything about that!”

And so it went. I told the students this material should have been covered in the previous course, but since it obviously had not been, we would back up and start with Analysis of Variance and other topics they should have learned in the previous course. At the end of the lecture, one young woman stayed behind. She said,

“I just had to say this in defense of Professor X. They may not have learned all of those things last quarter, but I was in that class and he sure the heck TAUGHT all of those things!”

The truth of the matter is that the great majority of our students remember very little of the information we teach them, no matter what we teach or who we are. Try this exercise with some friends who have been out of college a few years or more. Ask them to name all the courses that they took. If they are like most people, they can’t even remember the NAMES of every course much less what they learned in them. Even better, pick a random course, outside of that person’s major, and ask what was taught in it. If you are lucky, they can tell you one, maybe two facts.

Even more humbling after several years as a professor, I moved from academia to what my mother refers to as ” a real job” in the corporate world. When I was doing what everyone does to move up in rank, get tenure and generally prove their worth as a human being in the university world, i.e., publish articles in refereed journals, I, and my colleagues, were convinced that this would work its way down to those in practice in our fields, be it business, education or whatever. When I mention this to friends who are in business, they laugh in my face (strangers feel they need to be polite to you). I have to admit that in over twenty years running a business, the number of business articles I have read that helped my business were startlingly minute.

I have given hundreds of lectures on probability, p-values, power, the normal distribution, multiple regression, standardized beta weights, etc. The vast majority of people in those lectures were graduate students in social work, public policy, education, psychology, history, speech pathology and other majors but definitely NOT mathematics and statistics. In a development of which I disapprove, many graduate students can now get a masters or even a Ph.D. with only one course in statistics and research methods. Incredibly, my disapproval has NOT caused universities throughout the country to reverse this trend. Yes, I can hardly believe it either.

These graduate students, many of them long since graduated, are now making policy, managing programs, running companies and awarding grants. Many of them are very intelligent, logical and extremely knowledgeable about their content area, whether it be speech disorders or social security. What they are not is statisticians. They need to be able to make sense of statistical data and they need to be able to do it better than most of them can now.

Ironically, given the amount of time we spend on probability and hypothesis testing in most statistics courses, many of their decisions do not hinge on generalization to a population. It reminds me of a story someone told me recently about a presentation to a local school district. The speaker discussed the differences between schools in low income and higher income areas, correlations between various school factors and income, and talked at length about p-values and generalization to the population. The superintendent asked,

“What are you talking about? You have all of the records of all of the students in our district – or over 98% of them, anyway – this IS the population. I’m not interested in the rest of the U.S. or the world. You HAVE the population.”

In one or two semesters, I cannot make a person a statistician. I can’t even convince them to regularly read articles in refereed journals, and, if I am honest about it, most of those articles were written just so people could get tenure and really aren’t that useful anyway. What I hope I can do is enable him or her to take data and tell a useful and correct story. Here is a very simple example from a real project. The BP Project (not its real name and not affiliated with British Petroleum) received $1.5 million to recruit and educate teachers for bilingual students. The first thing the Project Director wanted was a picture of the type of students being recruited for the project. At the time when this snapshot of the data was taken they had admitted 408 teacher candidates over a five-year period.

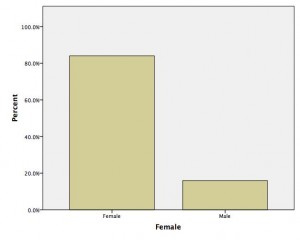

The first thing we can see is that the students are overwhelmingly female. That isn’t surprising since most teachers are female. Although increasing the number of males in teaching isn’t one of the project goals, the director is concerned about these results. She feels that many of the students in the schools where her graduates teach don’t have enough male role models and a discussion ensues with her staff about whether they should be trying to recruit more male students.

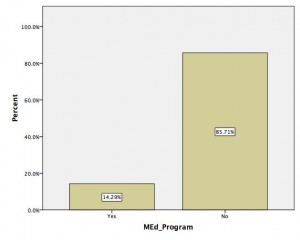

The university also has both a joint credential – masters degree program that students may elect and a regular teaching credential option. In looking at the proportion of students who choose the Masters in Education option we can see that it is a minority, less than 15%, who select the masters program. Although this is more than the 10% at the university as a whole, the director feels that her students could do better and discusses with her staff options for increasing the number of students who make this choice.

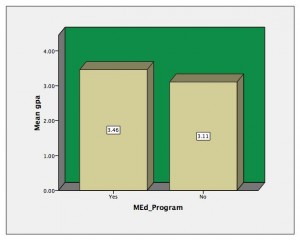

The next question she wants to ask is why some students select the masters program. Are those who choose the masters program better academically, as measured by their GPA? Are the ones who did not choose the masters program academically sub-par? As we can see from this chart, there is difference between the two groups. In general, when I tell clients,

“The F-statistic for Levene’s test of equality of variances was significant at p < .01. Therefore, you have a t-statistic of 7.3 with 135 degrees of freedom with a p-value of less than .001."

They do not find it very helpful, even though I personally think that is very useful information. (Sadly, I have found that people are willing to pay for what THEY personally find useful and aren’t that interested in whether or not it is crystal clear to me!)

So, I produced this graph using SPSS, which shows that the average student who is in the regular credential program has a GPA of 3.11 , above the 3.0 minimum for admission to the graduate program. The director found this very interesting. She wanted to know why, when the average student who was getting a credential could qualify for the masters program why more did not choose this route. I have no idea. She decided to meet with her students and former students and ask them. On the other hand, it is clear that the masters-credential students do have a higher GPA – nearly 3.5 versus 3.1 – and that this is probably significant in the practical as well as the statistical sense.

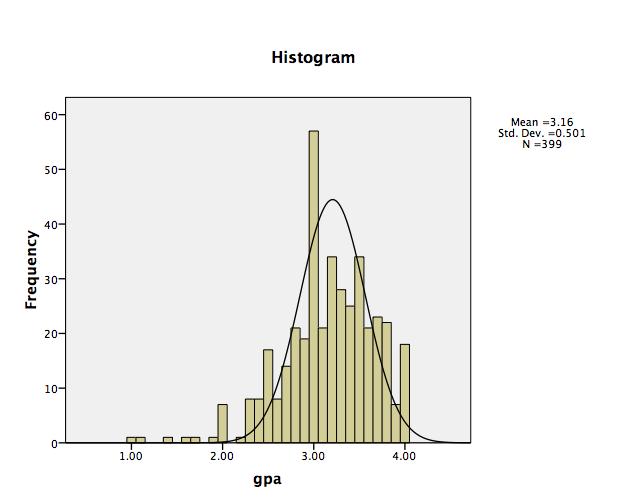

Given that this is a program designed to serve disadvantaged students, there have been mutterings from other faculty members that these students do not meet the university standards. This irritates the director for many reasons, not the least of which is that the program is for teachers to serve disadvantaged students, not necessarily teacher candidates who are disadvantaged themselves. She wants to look at the overall grade distribution.

This graph tells her several things. First, it tells her there are probably a few people who had data entered incorrectly because it is very unlikely anyone was admitted with a 1.0 GPA. It looks like maybe 1- 1.5% of the data have errors. I recommend she check that out. Second, the average student has a GPA of 3.16, substantially above the cut-off of 2.50 for the credential program and even above the 3.0 cut-off for the masters program. Further, the GPA distribution is very skewed, which is a good thing, in this case, and expected for a selective program. The overwhelming majority of the students exceed the minimum GPA cut-off.

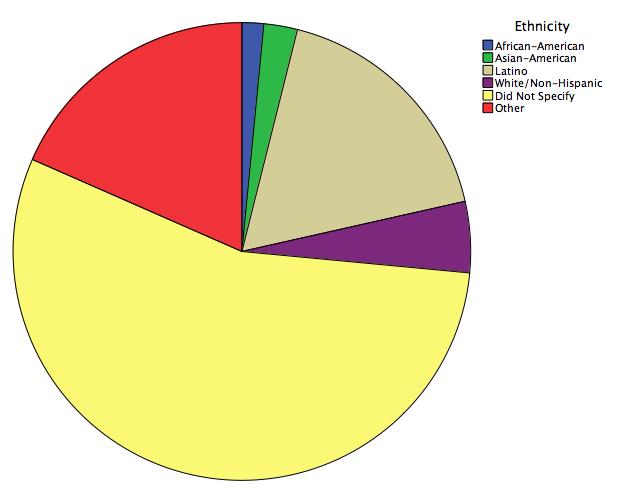

The final question the director had was about ethnic distribution of her teacher candidates. The university is predominantly white, non-Hispanic but she wondered whether a program designed to prepare teachers of bilingual students might attract more Latino and Asian-American students. This chart produced an interesting picture and one that suggested something wrong with the data.

The most common category is did not specify and the second is “other”. Looking into data collection problems, it was found that, in the initial year of the project, ethnicity was not asked on the student information form. So, to the extent that the first year ethnic distribution may have been different from later years, these data are biased. Was ethnic distribution different the first year? We don’t know.

Even in years the question was asked, many elected not to answer. A lot of hypotheses were offered as to why this was the case. Possibly non-Hispanic students felt they would have less chance of being admitted to the program and did not answer this question. When the staff followed up with some alumni they were told that, in fact, students did expect to experience “reverse discrimination” in the program and were pleasantly surprised this did not occur. Why did so many students list “other” as ethnicity? Some were mixed ethnicity, e.g., African-American and White and did not feel either category fit. Some were Native American or Filipino. Others we have no idea why they put down other. Given the questionable validity of the data, the director was cautioned against using these results to draw any kind of conclusions about the ethnic make up of the program participants.

One course I do remember from graduate school over twenty years ago was Questioning and Teaching, taught by J. T. Dillon, the author of a book by the same name. I haven’t seen him since and I doubt he’d know me if he tripped over me. I do remember a question he asked though, and my answer. He wanted to know:

“How do we know if we have taught someone something?”

I said,

“I think I have taught a person if I have given them the answer to a question they have been wondering about. If it isn’t THEIR question, they probably won’t pay any attention to it and I’m sure they won’t remember. If I don’t answer their questions, I’m just a person who stands in front of a room and talks a lot.”

He repeated,

“A person who stands in front of a room and talks a lot. Young lady, do you realize you’ve just given the description of most of the teaching that occurs in this country.”

I didn’t have an answer to that.

One Comment