Whatever happened to graduate research?

I read this recently in a powerpoint that came with a research methods textbook

If answering the study question adequately requires the use of elaborate analytic techniques, invite a statistical expert to serve as a collaborator and as a coauthor on the resulting paper.

I was so non-plussed that I looked up the word non-plussed in the Merriam-Webster dictionary

a state of bafflement or perplexity … to be at a loss as to what to say, think, or do

Um, this is a research methods COURSE, for graduate students, no less, and your advice to them in doing their research is that if it gets too hard they should find someone else to do it for them? This is not limited to one text or one school, either. At two universities where I have worked, both of which are well-respected and grant doctoral degrees, doctoral students, and post-doctoral students are asked before beginning their research,

Do you have a statistician?

In teaching statistics, I have been asked by doctoral students from multiple disciplines,

Why are we learning this when we are just going to have a statistician do it for us?

Obviously, research no longer means what I thought it meant. I thought that the process of research was that you formulated a question that interested you, you read the scientific literature on that question, generated a hypothesis, collected data from a sample, analyzed that data, evaluated your results and wrote a conclusion. Now, not only is it acceptable, but encouraged to have someone else analyze your data and tell you what it means. I find that perplexing.

This is not how it was when I was in graduate school. Back then, data were analyzed using computer software that ran on mainframe computers, or sometimes mini-computers. A mini-computer was not like an iPad mini. It was taller than me. Some of our data came on tapes which we had to walk across campus and load on to the tape drives ourselves, as we were lowly graduate students and it was assumed we had nothing better to do with our time. Fortunately, I was at the University of California by then and no longer at the University of Minnesota, where crossing campus could require skis. I did some consulting writing code for the data analysis for my fellow students, enough that caused the dean to call me into his office and ask me what I was doing and give me strict instructions, along the lines of

This is not how it was when I was in graduate school. Back then, data were analyzed using computer software that ran on mainframe computers, or sometimes mini-computers. A mini-computer was not like an iPad mini. It was taller than me. Some of our data came on tapes which we had to walk across campus and load on to the tape drives ourselves, as we were lowly graduate students and it was assumed we had nothing better to do with our time. Fortunately, I was at the University of California by then and no longer at the University of Minnesota, where crossing campus could require skis. I did some consulting writing code for the data analysis for my fellow students, enough that caused the dean to call me into his office and ask me what I was doing and give me strict instructions, along the lines of

You can write their programs for them, since this is not a computer science Ph.D., but that is all. You are not to comment or assist in any way with research design, writing their data collection instruments, choosing what analysis to do nor interpreting that analysis. When a person receives a Ph.D. from this university it is supposed to mean that they know how to conduct research, not that they know where to find someone to pay to do their research for them.

It seems that the tables have turned quite a bit. Even my least quantitatively oriented classmate back in the 1980s was probably equivalent to the average “statistical consultant” today. That is, they passed at least four graduate level statistics courses that required both a paper and a final exam with questions like, “How is Analysis of Variance related to stepwise discriminant function analysis?” This was true whether your Ph.D. was in education, business or psychology, because it was assumed, for example, that if you were going to place students in special education because they scored two standard deviations below the mean you should have a definite understanding of what a standard deviation was, what a normal distribution was and where two standard deviations fell on that distribution. Furthermore, as a superintendent or other school administrator, it was expected that you could evaluate the research literature (hence being skeptical of stepwise methods of all types).

It seems to me that what is required for a doctoral degree has been significantly watered down.

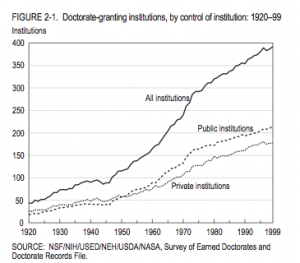

This chart shows the growth in doctorate granting institutions from 1920-99. The trend has continued. When I entered graduate school for my Ph.D. in 1985, there were 337 doctorate-granting institutions in the country. Now there are 418 – a growth of 24% over the past 29 years, on top of what had been, as you can see from the chart, a pretty steep growth rate for the 25 years or so prior to that time.

This chart shows the growth in doctorate granting institutions from 1920-99. The trend has continued. When I entered graduate school for my Ph.D. in 1985, there were 337 doctorate-granting institutions in the country. Now there are 418 – a growth of 24% over the past 29 years, on top of what had been, as you can see from the chart, a pretty steep growth rate for the 25 years or so prior to that time.

Who is teaching all of these new doctoral students? Well, in many instances, it is a horde of very part-time adjuncts. I don’t think adjuncts are necessarily poor teachers – in fact, I make it a point to teach at least one course a year myself – but I am aware of doctoral programs that are run with only ONE full-time faculty member. Given the paucity of human resources, it is no surprise that there is no one around to individually mentor the students in their research. Now, we are entering an era where those students who are graduating with very little research experience are themselves teaching doctoral students. It is a case of the very near-sighted leading the blind.

All of this is making me wonder where they are going to find those statisticians and how well-trained they are really going to be. I just finished with what will probably be my last student project for the next few years – no reflection on that student, or the other four students I worked with over the past two years, all of whom were a perfect delight – but my schedule is completely booked through October, 2015. Almost all of the really good statisticians I know are in the same boat.

I don’t have an answer to any of this. I am non-plussed.

> Why are we learning this when we are just going to have a statistician do it for us?

Good luck.

I was recently asked (as an unqualified statistician) to do some academic statistics.

I pointed out to the group leader that, although I could do the work, I don’t have any formal qualification in stats.

He said: “Don’t worry. We have an academic statistician who will put his name on the work; he just doesn’t have time to actually do it.”

Whoa! I would NEVER put my name on work I did not do.

Playing devil’s advocate here, and I certainly don’t know much about the PhD culture (then vs now) but could it have anything to do with the fact that fields are becoming increasingly more specialized?

The PhD program my boyfriend is most interested in at UC Irvine is an interdisciplinary program that requires a year of study before hooking up with an adviser from whichever program most closely suits your research interests. I think he’s looking at biology/mathematical modeling (like modeling diseases or tumors), but other choices for that same program include physics and computer science as well (and engineering too?). I don’t think such a thing even COULD have existed while you were in graduate school, could it have?

The more we learn, the more specialized advanced degrees will have to become, which will necessarily limit the breadth of topics studied, won’t it?

Well, I’ve never helped someone pass a course, but I do consult with people who are doing their dissertations and I don’t think that’s odd.

When they graduate, even if they go into research, their research team will likely have a statistician (and I used to be such for several research teams).

I insist that my clients know enough to be able to explain what we did and why we did it; but I don’t see that getting a PhD in, say, psychology, should require being an expert in multilevel models.

I think one thing that has changed in the last few decades is that the variety of statistical techniques that are commonly done has increased tremendously.

It is true that some people did, say, factor analysis “by hand” but this involved hiring LOTS of people to do the calculations on old style calculators. What grad student could do that?

That’s where we somewhat disagree, Peter. I think that if your dissertation involves multi-level models then you SHOULD be an expert in that. If it involves survival analysis, you should know that. You don’t necessarily need to have a broad knowledge of statistics, but at least what is in your dissertation, you should know in great detail because it is supposedly YOUR research. And truly, many students can barely explain their own dissertations, which troubles me.

I’ll never forget being in the room for a talk by a post-doc who was applying for a research faculty position at a university. The woman presented some paper she had submitted recently, and the head of the department asked how she had handled missing data. She said “we assumed they were missing completely at random.” When the head asked the justification for that assumption, or if they had done any sensitivity analysis with imputed values, etc, the woman just said “well, that’s what the statistician told me.” And it felt to me like all the air was sucked out of the room. Wanted to stop the talk right there and just yell, “Next!”

Oh, my God, Quentin –

My jaw dropped when I read that, literally. Yet, as I said, there is a whole cohort of people who is being educated to believe that is a perfectly fine answer!

Samantha –

We actually had interdisciplinary majors like psychobiology back in my day, and you could even create your own major. These were second in popularity to Dinosaur Studies (I’m kidding – Dinosaur Husbandry was actually more popular.)

If those people really were studying disease models instead of statistics, I might agree with you. However, they are usually taking classes on the differences between post-positivism and positivism and which theorist represents which framework – or something like that which I would have to pretend to care about to describe adequately.